Dark Ages Re-Creation Company

Dark Ages Re-Creation Company

Note that the original presentation of this paper was illustrated with slides. To give a feel for this, there are a number of small thumbnails included along with the body of the text. Each of these can be clicked to bring you the full sized image. (There also may be some repetition of these images from elsewhere in this series of information.)

"From the Fury of the North Men, Oh Lord, deliver us..." spoke a terror stricken English priest in the early 800's. The Viking raiders that seemed to virtually explode out of Scandinavia starting in the last decade of the 700s were just the most visible element of a complex culture. The Norse people of Sweden, Denmark and Norway, shared a common religion, world view, material culture, technologies, writing system, and related languages. All of these were quite distinctive from those of the peoples living to the south and west of them. Their characteristics of physical toughness, fierce individuality, skill in arms and nautical brilliance enabled them to have such an impact on the rest of Europe that the period there that stretches from 793 to 1066 is commonly referred to as the Viking Age.

Some time in the last decade of the first millennium, the first groups of Norse explorers arrived on the shores of North America. Like other Europeans who would follow centuries later, these bold men and women were seeking resources, wealth, and perhaps were driven by the desire to make their mark. They would delineate the furthest western expansion of a culture already famous for its daring voyages. They would leave little behind them when they left eastern Canada, a mere hand full of artifacts and a the ruins of a couple of houses. Most importantly, the tales of their adventures would be retold for generations until these took on the form of legend, the core of truth lying encased within the story tellers art.

'Kettil Einarsson' on board the 'Viking Saga' - 1995*.

In the early 1960s, the Norwegian researchers Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine would use the clues buried in these same tales to help in their search for archaeological evidence of the Norse in Eastern Canada. Their investigations would eventually lead them to uncover the remains of a group of turf houses at L 'Anse aux Meadows in Northern Newfoundland. Along the grass covered terrace that parallels the shore they excavated the remains of a total of eight structures of a type also seen in Iceland and Greenland. Although the actual number of artifacts was small, the remains of a bog iron foundry, soapstone spindle whorl and bronze ring headed pin all pointed to Norse occupation. Carbon 14 analysis of wooden and charcoal fragments placed the date of the site's use to around 1000 AD. Taken altogether, the only conclusion that could be drawn was that this was an outpost built by the Norse, about the time of Lief Eirikson.

The site at L 'Anse aux Meadows became a Canadian national park in 1977, and a year later became the first UNESCO World Heritage Site. In 1980 Parks Canada reconstructed one of the main longhouses, along with two of the smaller buildings, just north of the location of the original structures. Latter a modern interpretive centre was constructed on the bluff that rises about 500 m in shore from the ruins. This building houses artifacts from the site, various reproductions that help illustrate the 'World of the Norse', a small theatre, and administrative facilities. Educational services for the visiting public at this point were provided by a staff of trained guides. Despite the small physical size of the site, and its remote location at the very tip of Newfoundland's Great Northern Peninsula, over 20,000 people visit over the three month operating season each year.

Overview of the occupation site at L' Anse aux Meadows.

In 1996, Parks Canada sponsored a two week demonstration of a living history program utilising costumed interpreters. "The Norse Encampment" had been developed by myself as a special educational presentation that was originally part of a community Mediaeval festival (in Orangeville Ontario). The program at L 'Anse aux Meadows utilised a core group of four professional interpreters, surrounded by a collection of approximately 250 individual artifact reproductions. The costumed staff utilised a number of different interpretive levels and techniques to bring the Viking Age to life. On the part of Parks Canada, it was an opportunity to evaluate the potential suitability and usefulness of a living history program at very low cost. For myself and the interpreters involved, it was a chance to refine both the program and our skills. Taken altogether, the Norse Encampment program proved a resounding success, significantly increasing admissions and visitor satisfaction with the site.

'Bera Quickfinger' at the orginal Norse Enacampment, Orangeville - 1994

The crew of 'Raven's Wing' on the beach of Epaves Bay - 1996

With the utility of living history as part of the educational programming at L 'Anse aux Meadows demonstrated, work was started on a regular seasonal presentation. I was contracted by the Viking Trails Tourism Association, working in partnership with Parks Canada and Human Resources & Development Canada. The entire interpretive program was to be designed and implemented, the required reproductions had to be created (or commissioned), plus the training of six local people as the historic interpreters. The "Viking Encampment" opened in mid June of 1997, and remains a daily feature at the site into its second operating year. Almost universally, the visiting public remains enthusiastic about the work of the interpretive staff. More importantly the program has also been seen by a number of researchers and archaeologists familiar in the Viking Age, who all have reported positively on both its historical content and educational value.

The mission of the Viking Encampment, however, was not to simply to entertain the public, or to attempt to create a simple 'snapshot' of a specific place and time from history. The intent of the re-enactment was to provide the museum visitor with an insight into the overall culture of the Norse, to create an impression of what a people and their world were like. A collection of reproduction artifacts would be placed in context, and seen in daily use. Costumed staff would employ an number of interpretive levels, portraying characters which are bolder than life to better illustrate specific attitudes. In this way, everything that was included in the presentation, and how each element was employed, was part of an overall design. Reflecting on the process of researching, creating and implementing this interpretive program may prove of interest and value to museum professionals at all levels, from the working interpreter to the academic. The lessons from the Viking Age include those that are practical, technical and theoretical - and sometimes things totally unexpected!

'Astrid Blue-Eyes' tends the fire in the main hall - 1997*.

One of the overall problems with designing any living history program lies in deciding just which original sources will be selected as the prototypes on which not only overall content, but even individual physical objects, are to be based upon. In any translation from 'pure' archaeological and historic research into public programming, a wide number of factors interact to influence what is placed before the public. Many of these effects are only slightly felt, if at all, with a site portraying life of the Settlement period, a 'mere' 150 years ago. First of all, there is the problem of how the accidental nature of artifact preservation never leaves much more than a shadowy outline of the original life of any site. What controls the survival of an object often has little to do with its cultural context within the original period of study. Often the most common objects are actually the least likely to survive, do to excessive wear, less durable materials, or the lack of care given to the everyday. One obvious solution is to examine materials from a number of related sites, thus to provide a larger number of physical samples to chose from. The problem then becomes one of judgment. How far from the chosen focus, in item, geography, or even cultural details, does one look? Obviously, the further from your target site you move, the more likely that the references provided by other locations will not apply. Original document sources become not only harder to find, but also increasingly unreliable, especially in fine details, the further back in time one goes. Unlike other North American museums, that rely heavily on original documents of all kinds for their sources, any program dealing with the Viking Age must be based almost solely on archaeology.

Artifacts from L' Anse aux Meadows : Wooden disk, thought to be a pail lid...

and one of dozens of 'boat rivets'.

These aspects were especially troublesome in the case of the Viking Encampment program for L 'Anse aux Meadows, where a full 1000 years has passed since Norse occupation. As has already been stated, the physical remains uncovered on the site were extremely limited both due to the early date of the site and also the marginal nature of the original occupation. There were only a dozen or different types of items found. (Considering groups of like objects as consisting of a single type: for example there were over 100 rivet fragments recovered, but they primarily consist of the same 'boat rivet' type.)(2) Obviously any attempt to re-create the daily life in Vinland would necessitate the examination of a number of other locations. In a program such as this, every attempt was made to focus as closely as possible on the physical culture of the Norse who made up those ship crews at the turn of the first millennium. To this end, the first likely source to be considered would occupation sites from the Norse colony on Greenland, which itself has over a 400 year occupation record. Unfortunately, these also are very limited as artifact sources, for many of the same reasons as is the case at L 'Anse aux Meadows. The next step would was Iceland, the original homeland of many of the potential Greenland colonists. In the end it in fact it proved necessary to utilise a very wide selection of archaeological sites for artifact and cultural prototypes. To provide for the original artifacts required as samples for tools and domestic ware it was necessary to examine materials from major sites such the Oseberg (Norway, early 800s), Coppergate (York, England) and Woods Quay (Dublin, Ireland - both late 900s), and Mastermyr, (Norway, dated c. 1150 AD). Individual sample items ranged from sites throughout the Norse world and the Viking Age. Where ever possible, prototypes were selected from a physical chain that started in L 'Anse aux Meadows and extended back to Norway, and as close the date of 1000 AD as was possible. For the Viking Encampment, the artifacts chosen for reproduction represented an amalgamation of items from all the disparate locations listed above. The objects selected were all of common types, widely used throughout the duration and geographical spread of the Viking Age. It should be noted that it cannot be proven that this exact selection of goods was in fact specifically present at L 'Anse aux Meadows in 1000 AD. It is felt, however, that despite the physical and temporal spread utilised, the selection made was reasonable within the general context of Norse culture and custom.

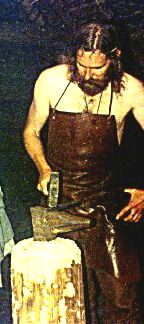

A graphic example of this process in action can be seen in the selection method employed for the blacksmiths tools that were included in the Viking Encampment. The working of iron is one of the most important parts of the L'anse aux Meadows story. The remains of bloomery slag, a charcoal pit and what has been interpreted as a specially constructed foundry building all point to the conclusion that the Norse processed local bog iron into approximately 3 kg of metallic wrought iron. (3) The discovery of these iron remains was one of the proofs that the site was European in origin, rather than constructed by Native North Americans. It also marks the first documented processing of iron on the continent, predating the next claimant to this event by over six hundred years (Jamestown, Virginia at about 1615). Obviously, the production of iron by the original Norse inhabitants was an important point to be illustrated within the interpretive program. The simplest way to introduce this subject was through the inclusion in the display in a set of blacksmiths tools.

The problem arose in the search for Viking Age prototypes. The basic tools of the smith; hammers, tongs and punches, are relatively common in Norse archaeological finds, so finding suitable prototypes for these was not difficult. Artifact reproduction was made simpler by the fact that the basic shape, size and construction of these basic tools has remained almost unchanged through the centuries. The two major pieces of blacksmiths equipment, the bellows and the anvil, presented the major challenge in determining prototypes.

Viking Age bellows, used to increase the temperature of a charcoal forge or smelting fire, exist only as fragments - when at all. Not too surprisingly with an object constructed of wood and leather, damaged bellows plates were likely turned into fire wood when worn out to be serviceable any longer. In the end the prototype for the bellows was taken from an illustration of a blacksmith at work carved in wood on the stave church at Hyllestad, Norway, dated to the late 1100s. In this case the best available historic source is a secondary one, lacking in detail, and in fact outside of the time period under consideration.

The bellows, bog iron, and collection of blacksmith's tools...

and the reproduction anvil from the Norse Encampment - 1997.

Norse period anvils are uncommon verging on rare, especially when one considers the abundance and quality of forged objects from the period. Most Viking anvils tend to be of small size, roughly ten cm cubes, and range around five kg in weight. Even so, this mass of iron represented a considerable investment in raw metal, and the physical labour involved in working a block this size was considerable given the technology of the period. (In many cases flat topped rocks were more likely to be used as work surfaces by Norse blacksmiths.) The prototype anvil used for the Encampment was actually an unusually large and elaborate one by period standards. The original artifact selected weighs about 15 kg, was found at Novgorod, Russia, and dates to about 1000 AD. (4) My interpretation of this specific artifact is that it likely was the equipment of a master smith, and certainly would have been an extremely 'expensive' one, both in terms of materials and effort to create it. With the marginal nature of the outpost at L' Anse aux Meadows, there is no reason to assume the presence of the kind of highly skilled craftsman that the presence of such an object indicates. Why then was this artifact chosen as the prototype instead of something less elaborate?

A figure in the static display at L' Anse aux Meadows.

'Kettil' working metal in the small turf house - 1996.

The main reason lies in the earlier display work done at the site in conjunction with the main interpretive centre in the early 1980s. Along with a number of resin cast copies of various period objects there were several dioramas produced. These contain a number of human figures (strongly influenced by the illustrations of Ake Gustavsson)(5) that spotlight the artifacts found at the site and places them into context. One of these figures is posed working at an anvil which itself is clearly based on the sample from Novgorod mentioned above. Despite the fact that I believe that this style of anvil, and the master smith it implies, never was physically present at L 'Anse aux Meadows, this object was again used as the prototype. This was done not to further validate the work of earlier designers, but to preserve the continuity of the exhibits over the entire site. The average museum visitor will not have the background in detail to appreciate the differences in interpretation and research that would be represented by the inclusion of one style of object over another. They will however, immediately notice and comment upon any discrepancies in information or presentation between one source at the site and another.

A very good example of the difference between a scholarly and an practical approach to re-creating an artifact can be shown by considering the turf houses built at L 'Anse aux Meadows by Parks Canada. The original house walls revealed by archaeology at the site are little more than the collapsed remains of the very bottoms, with lines of post holes to indicate the positions of the original framing timbers. When the reconstructions were carried out in the 1980s, the remains of the Stong House from Iceland, and its reconstruction, were used as the prototypes for the missing upper sections. Stong is basically contemporary to the construction at L 'Anse aux Meadows (buried by volcanic ash in 1104) and is also from roughly the same cultural group. (It was Icelanders who made up many of the original Greenland settlement, hence the members of the Vinland expeditions.) The one real, and as it turned out extremely important, difference was in the physical positioning, and hence local environments, of the two locations. The Stong farm lies about 50 miles inland, and the prevailing winds blow from the west. The door of the Stong house is on side of the building towards the prevailing winds at the site. The upper portion of the structure was not preserved, so the exact location of the smoke holes originally used here is not known. When the reconstruction was done, the smoke holes were located in the centre of the roof - for no better reason that it proved the easiest for the contractor doing the work! In existing houses in Iceland, built in the same tradition as these ancient structures, the pattern is to place the smoke holes in the down wind slope of the roof, just down from the peak. As the wind rolls over the roof, it tumbles, creating an area of relatively low pressure just above the smoke holes which (with properly fitted covers) helps extract smoke from the cooking fires set in the central floor of the building. By opening the door, the prevailing wind would be pushed into the building and up and out the smoke holes, if even more draft was required.

The physical environment at L 'Anse aux Meadows is quite different. The houses are built along the shore, almost close enough to toss garbage from the doors straight into the ocean at high tide. As well, the site is located at the very tip of the Great Northern Peninsula, and although it is at the base of the small Epres Bay, the location is basically surrounded by water on three sides. Consequentially the winds at L 'Anse aux Meadows are constant, strong - and seem to shift direction every twenty minutes. Utilising the Stong / Iceland prototype, the smoke holes were placed on the eastern side of the roof - away from the 'prevailing' westerlies. The door openings were also on the east, conforming to the outline of the original building outline, although a door originally found on the western wall was omitted in the reconstruction. When fitting the wooden board covers for the smoke holes, the panels where hinged to swing inwards - despite the fact that it is far more practical to have them swing out and up. This was done for modern day security considerations, it was easier to secure these inward swinging covers. The problem that these related factors created was not immediately obvious, as the buildings were only occupied briefly by staff and visitors during guided tours, and fires were only built inside occasionally.

With the constant occupation and day long use of fires for light, heat and cooking demonstrations by the staff during the new interpretive program the problem with the building's layout became instantly obvious. Well over half the time, an offshore east wind was forcing smoke back down through the smoke holes into the building interior. With the only doors on the same side as the smoke holes, there was no way to create a cross draft to clear the room. (This was further exaggerated by the fact the doors had to be kept constantly open to receive the public.) With the covers swinging inwards, not only was the frequent rain able to pelt the interior, the roll of air from any west wind was actually pushing smoke back inside as well. Taken altogether, it was obvious that the original structure would have to been equipped with smoke holes on both sides of the roof - and with covers that swung up. Constant tinkering with the position of the covers, and just which combination of smoke holes and doors would have been opened, would have been required to allow the interior rooms to remain habitable. It seems clear that pure scholarship was hardly up to the challenge presented by practical application in this instance

The exterior of the main turf house, looking north (the sea is about 50 m to the left). Note the position of the smoke hole on the right side (east) of the roof, and the billowing of the tent canvas in the wind! 1996

'Astrid' inside by the main fire, just below the smoke hole seen in the other image. Note the haze caused by smoke that is trapped inside the building - 1997.

Even with the most ideal of document and archaeological sources available, the problem of just how the available information will be interpreted remains. Every museum presentation is effected to some degree by 'point of view', at the hands of everyone involved in the production. Ideally, every attempt to minimise the impact of external biases should always be made. In reality, the effects of editorialising raw information range from the subtle to the blatant, the accidental to outright propaganda. In the very worst of cases, presentations are specifically designed to vindicate current political opinions - regardless of what the 'pure' history might really be. (We are all aware, of course, that all forms of human endeavour suffer from this problem, the raw research on which other museum work is based is not immune itself.) Even with the problem of accidental (or deliberate) distortion to reinforce institutional or personal bias aside, there remains the question how to provide for the personal attitudes of the museum visitor themselves.

For the Viking Encampment program, the first of these filters can be seen in the defining mission statement. The objective of the program is to "...represent aspects of daily life as it would have been carried out at the Vinland outpost and to provide insights into the larger framework in Norse culture in general." This is somewhat different that the less precisely defined objective of the L 'Anse aux Meadows NHS, which centres on the specific history of the site itself. This living history presentation attempts to do much more than just portray the lives of the original Norse inhabitants. It also is designed to illustrate the broad outlines of Norse culture in general. The historic reality of the Vinland outpost is used as a spotlight that shines back towards Greenland, Iceland and the Scandinavian homelands. As might be expected, some of the shadows cast are distorted, with fine details obscured the distance.

A special problem encountered in designing the overall program for L 'Anse aux Meadows is that the time period is so remote, and the culture of the Norse so shrouded in legend, that little could be expected by way of even basic background knowledge on the part of many visitors. For most adults, the world of the Vikings is one of bloodthirsty raiders in horned helmets, drinking, raping and burning churches. It is an image born of bad movies, Robert E Howard and football team logos. The recent generation of Canadian school children at least have some idea who the Vikings are, and where Vinland is. Most other living history programs are not faced with the situation of having so many of their visitors knowing so little when they walk through the gates (and most of that being wrong!). Curiously, a certain portion of the public is extremely well informed, and have made a very major travel commitment to visit the museum. Every year a significant number of Scandinavians, academics and serious amateur students of the Viking Age make the 800 km round trip from Corner Brooke up to L'anse aux Meadows specifically to visit the site.

From the initial concept of creating a historical presentation centred on the Norse exploration of Vinland in 1992, there was no doubt that using the framework of living history would be the best method. The underlying objective of any living history program is not to illustrate the latest scholarly research in detail. Rather, the purpose is to provide the general public with a basic understanding of 'what it was like'. The impact of even the simplest living history presentation can be enormous. The creation of an entire environment based on the historical model allows for full utilisation of all of the senses. What started as dry research on paper is now transformed into a living reality with elements that can be accessed, at least in part, by anyone. Language is transcended by sight, educational barriers by physical demonstration, physical restrictions by touch. Often obscure information becomes clear through context. The greatest achievement of any living history museum is when it provides the spark of interest that leads a visitor to further studies on their own. Despite the special challenges that producing a creditable re-creation of the Viking Age presented, there were in fact several advantages that quickly became apparent.

Posed figure in the static display at L' Anse aux Meadows Visitor Centre.

'Bera' at her mending by the fire in the turf house - 1996.

First, all of the individual objects used in the presentation would be modern reproductions, rather than actual artifacts. Living history museums are especially dependent on the use of physical objects to create the illusion of the past. Virtually everything within the 'historic area' contributes to the effectiveness of the presentation, from buildings to type of garden plants - even to such intangibles as the perfume used by the staff. (The atmosphere of Black Creek Village in Toronto as a Victorian crossroads town is shattered by the fact it now lies directly under the flight path of the busiest airport in Canada.) Within individual institutions, the practices centred around the collections can vary considerably, with a mixture of both period artifacts and modern reproductions being most common. Staff treat artifacts in a manor differently than reproductions, and certainly not the way the same objects would have been handled when they were new. Ideally, at least all the 'working' objects at any museum should be reproductions, if for no other reason than to preserve original artifacts for the future.

At L 'Anse aux Meadows, the physical setting is close to the same one that Leif Eiriksson would have seen centuries before. The compound that makes up the reconstruction has been positioned very close to the remains of the original structures, just another 50 meters or so along the same marine terrace. The main museum building sits on the top edge of the bluff that forms a natural boundary along one edge of the site, thus placing it a good 500 m from the reconstruction. The small cluster of houses that makes up the modern day settlement of L 'Anse aux Meadows is visible in the far distance, but are basically too far off to provide much distraction. Certainly the landscape is dominated by the shore and the ocean, which remain much the same as they always have been.

The major 'artifacts' on the site are the three reconstructed turf houses built by Parks Canada in 1980. These have been built with considerable attention to detail, and virtually all of the modern elements are structural, and thus hidden inside the walls. The use of essentially the same construction techniques as were employed by the original Norse inhabitants, along with utilisation of the same local materials, has produced a localised environment virtually identical to that which existed 1000 years ago. The immediate area around these structures is bounded by a withy fence that further serves to contains the action of the re-creation - and to focus the attention. (This fence was not actually present in the Viking Age, but is an addition based on types seen at other Norse farm sites.)

View of the reconstructed buildings enclosed by the whithy fence.

In the creation of the Viking Encampment, there was no question but that all the objects used in the presentation would be modern reproductions. All together, about 175 individual objects were produced. Many of these were detailed reproductions of specific artifact prototypes, others were consistent with type, with details derived from a number of sources. A number where more speculative in origin because there are no clear period samples to provide prototypes, for example the costumes worn by the interpretive staff. Generally, the objects used in the presentation can be considered to be fulfilling an intermediate level of experimental archaeology, where both form and function of the originals has been duplicated, but were raw materials and some forming processes employed were modern ones. (6) One of the huge advantages of utilising all reproductions is that they are not precious, in the way original artifacts can often be. This allows the interpreters to interact with the objects in a manor consistent with that used by the original owners. (A 'new' water bucket can be shoved aside with a foot, instead of being carefully lifted with both hands as an artifact would have to be.) Even more important, this also gave the visitor the freedom to physically handle the items, allowing for them to directly experience each piece for themselves. Over the first season only one object has suffered any significant damage from mishandling by the public, and one item was lost due to theft. This is a small price to pay for the incredible potential for interactive learning allowed through the use of these reproductions.

What remains of the bronze ring pin found at L'Anse aux Meadows.

The reproduction of the pin as used in the Norse Encampment, with an antler comb.

(Pin by D. Roberston, comb by S. Strang.)

When it came down to the actual manufacture of the objects, the real world of cost, availability and skills exerted its influence. The raw materials that were utilised, and how these were worked into each individual item, where determined by a web of what could be found, how it could be worked and how the final object was to be used. In the forming of the 'iron' objects, modern mild and carbon steels were substituted for the wrought iron used for the originals. True wrought iron is no longer commercially produced, so modern industrial steel bars were pre-profiled by hand to 'dress' them. All the forming work for the 'iron' work was done using traditional blacksmithing techniques, but employing what was essentially Victorian technology of large anvils and coal fires. (As opposed to the small block anvils and charcoal fires of the Viking Age.) The wooden objects were made of similar species as the original prototypes were ever possible, although of North American origin. Rough cut planks from a commercial sawmill were surface dressed to produce the required boards (rather than the Norse method of quarter split from logs). Modern commercial fabrics were used for the costumes, with care was taken in their selection to conform to period types. These were machine sewn not just for cost considerations, but also to better withstand the constant washing they would be subjected to. Other objects specially created with extensive use of hand fabrication techniques included: boots and other leather work, jewellery, and the water buckets and pails.

One of the great issues surrounding the use of living history museums has been the question of whether they are in fact able to accurately portray the past at all. The argument from the academic community has often been that such museums actually do more to distort the past than they do to re-create it. The quality of individual living history museums ranges widely, as does the size, scope and resources available to each. Poorly trained staff, sloppy workmanship, poor attention to details, (usually corners cut because of tight budgets) - all are used as proof of why living history is a questionable technique at best. Generally much of this disdain amongst academics is the result of a lack of understanding on their parts of just what the goals of living history programs really are. (7)

A large number of terms are used, often interchangeably, when referring to the various types of history based presentations seen at various museums. One often hears of "animators" being used, particularly by institutions in the United States of America. I define an animator as being a professional actor, hired to give a previously written and clearly defined performance. Generally the script will be delivered exactly as written, with very little modification between performances or possibility of interaction with the audience. It is quite possible that the content of the performance content and supporting props (such as costuming) may be extremely accurate. The animator may in fact have had considerable training, or has done personal research into details of period mannerisms and modes of speech, enabling them to do a very creditable job at re-creating the past. Based on personal skills, they may in fact be able to deviate from the prepared text to allow for interactions with the audience. Generally, however, this is in fact not the case, with staff being chosen for their acting ability, rather than for any historical knowledge that would allow flexibility. The presentations themselves tend to be theatrical, with bold drama emphasised more that what is likely a more boring reality.

A Historic Interpreter, on the other hand, is an individual who is trained in history rather than oratory. The interpreter will attempt to speak as a 'voice from the past' and carry on a direct conversation with the visitor. The precise amount of historic detailing engaged in is dependent on the interpretive level chosen, modified by a range of other factors. As might be expected, the depth of historic detail, of 'reality' in the eyes of the visitor, depends on a huge and complex web of facts must be instantly available to the interpreter. It is true that extremely good interpersonal skills, and a sense of creative drama, are also called for. There is no doubt that effective living history staff, especially those utilising higher levels of interpretation, absolutely demand the support of extensive training programs on the part of the institution.

'Thora of Meath' cooking flat cakes, a popular way to provide the public with a taste of the Viking Age - 1997.

'Astrid' gives direct hands on experiance with a reproduction drop spindle based on the stone worl found on site - 1997

As has already be stated, the Encampment project was always considered as an exercise in living history. That being said, the next thing to be considered was which level of interpretation would prove the most effective in presenting the Viking Age to the general public? As is so often the case, even the best laid plans seldom survive implementation without modification.

As it was originally conceived and structured in 1993, the original Norse Encampment was designed to make use of full role playing on the part of the interpretive staff. (Where the interpreters referred to the past as if it was current, with no references to the modern day, and with detailed characterisations.)(8) Although the staff involved in this initial program were certainly skilled and knowledgeable enough to maintain this approach, it quickly became obvious the public was not. As discussed above, the Viking Age is too distant and unknown, too much distorted by popular culture, to allow the general public much by way of points of reference to the period. As the presentation was modified in use to suit the demands of the visitors it was found that a kind of 'sliding scale' of interpretive levels was in fact called for. In practice this consisted of using a series of what were essentially short vignettes as role playing. Although the rough outline of each of these set pieces were understood by the interpreters involved, the actual content was not scripted, allowing for a more spontaneous (and realistic) delivery. These exchanges were seldom more that a couple of minutes in length, and would be followed by commentary given from the third person stance ('they did', with modern references). The general flow of the interaction with the public ranged between first person ('I did', given as a character type) and commentary. These methods were further refined during the 1994 presentation. As might be expected, this technique demands a great deal of both skill and flexibility on the part of the interpreter.

The Encampment program as was demonstrated in 1996, and as it continues at L' Anse aux Meadows, continues to make use of this system of varied interpretive levels. During the initial design and training phase of the project, a series of character sketches were written. These represent character types - rather than specific historic individuals, purposely designed to be 'larger than life' (almost caricatures) to make it easier to illustrate specific elements of the culture. Elements of the characters were determined by considering the personalities of the staff themselves. Once the characters were assigned, the staff have been allowed to flesh out many of the small details that breathe life into these persona. All this serves two purposes - making it easier for them to interact as 'real' people, and also giving them a sense of ownership in the characters. Because all of the main outlines are agreed upon, and many of the fine details are not, the public is often presented with several versions of the same story - creating a sense of inclusion into the personal relationships of this Norse crew.

'Thora' gives her slave girl 'Astrid' a questioning look - 1997.

An example of this in action is the complex web of relationships that exist between ship's captain 'Bjorn', his strong willed wife 'Thora', and her personal slave 'Astrid'. Thora has become fed up with Bjorn's endless quest for status and empty promises. His favouring of the young Astrid is the last straw, and she intends to divorce him - as soon as she gets back to civilised lands. Astrid sees her chance to become a free woman, but has to avoid the sharp tongue (and hand) of her mistress. Bjorn is blissfully unaware of it all. A visitor may hear from Astrid how hard her life is, from Thora how fed up she is, and from Bjorn about his next great venture. Along the way, it becomes possible to introduce the topics of slavery, status, trade, women's rights and law. In using this technique, there is no doubt that the 'true' image of the Norse at L 'Anse aux Meadows has been distorted. Remember, however, that the stated mission of the Viking Encampment is to illustrate the wider outlines of Norse culture.

Obviously, the success of such a method is highly dependent on the skills and knowledge of a well trained and professional interpretive staff. In the initial stages of the Encampment program, staff were drawn from the ranks of 'serious amateurs'. Many of them had some direct museum experience at various Ontario living history sites. All had undertaken long years, in some cases decades, of personal studies into the Viking Age, including the development of extensive craft skills. All had built up considerable experience in recreating historic characters as historic re-enactors. In this way, during the development stage of the program, stress could be placed on training for interpretive techniques and specific presentation methods, rather than for broad historical knowledge.

This situation entirely changed in 1997, with the implementation of the regular seasonal program at L 'Anse aux Meadows. The six staff required as interpreters would be hired locally, and could not be expected to have any previous education in history at all. As it turned out, none of them had even ever seen a living history presentation. Most had no more than a secondary school level of education, with an average of less than one year of an applied college program. There was a total of four weeks allocated for the staff training, three weeks in the class room and one week of direct supervision in front of the public. This is actually quite generous in comparison to many living history museums, where training is commonly measured in days rather than weeks. (It is similar to the six weeks training provided at the "Viking Adventure" in Dublin, Ireland, which re-creates the same period in history - and is the closest location of another presentation of the Viking Age.) Still, the demands placed on the staff were considerable, they were expected to soak up the equivalent of a university level Norse history course, plus the necessary hand skills, plus acquire the required interpretive skills. The training manual alone had over 200 pages!

It is to the personal credit of the staff members selected that they were able to achieve such a high level of historical knowledge and interpretive ability in such a short time. Like any significant museum site, the range of understanding within the visitor population ranges enormously. L Anse aux Meadows may exhibit an wider range than most, due to its strange mixture of remote location and World Heritage designation. The greatest number of the visiting public are 'local' - which in the case of rural Newfoundlanders means that the average educational level is fairly low. Most adults possess no more than a secondary school education, and the quality of even that is generally poorer than the Canadian average. On the other hand, the balance of the remainder have travelled well over 200 km (one way) specifically to come to this site - more for those who have made the 12 hour drive up the entire length of Newfoundland to visit the museum. About 3% have made the trip all the way from Europe, many Scandinavians consider the Vinland site of 'Leif's Houses' as much part of their history is it is Canada's. What this all means is that a large number of the public are knowledgeable on at least the outlines of Norse history.

Dawn Taylor (as Astrid) pulls a couple into her confidence - and into the World of the Norse - 1997

Mike Sexton (as Bjorn) "educates with a smile" as he spins a warrior's tale for visitors - 1997.

Mike Simons (as Kole) illuminates the techniques of Norse navigation with a direct demonstration - 1997.

There is no doubt that the remoteness of the Viking Age made the techniques of living history the most effective choice for presenting the broad outlines of Norse culture to the public. The creation of a new interpretive program for L 'Anse aux Meadows NHS was the result of a long development phase working towards an effective museum presentation. The Viking Encampment program faced many of the same research and production problems seen in the development of any new living history program. In the case of this re-creation of daily life in Vinland, many of these effects were greatly magnified due to the marginal nature of the original site and its extreme remoteness from modern times. These same factors illustrated the separation between the theoretical and the practical, creating a situation that results in the Encampment program often becoming an exercise in experimental archaeology. As with all living history programs, the final success of the presentation rests on the shoulders of the interpretive staff. Although the reproductions are of high quality, the design of the overall content sound, and the physical environment ideal, in the end it is the individual historic interpreters who breathe life into the Viking Age.